Case Digests for Assigned Articles of the Family Code

Articles 377 and

378.

Yasin V. Sharia

District Court

G.R. No. 94986, 23

February 1995

FACTS:

On 5 May 1990,

Hatima C. Yasin filed in the Shari'a District Court in Zamboanga City

a "Petition to resume the use of maiden name.” The respondent

court ordered amendments to the petition as it was not sufficient in

form and substance in accordance Rule 103, Rules of Court, regarding

the residence of petitioner and the name sought to be adopted is not

properly indicated in the title thereof which should include all the

names by which the petitioner has been known. Hatima filed a motion

for reconsideration of the aforesaid order alleging that the petition

filed is not covered by Rule 103 of the Rules of Court but is merely

a petition to resume the use of her maiden name and surname after the

dissolution of her marriage by divorce under the Code of Muslim

Personal Laws of the Philippines, and after marriage of her former

husband to another woman. The respondent court denied the motion

since compliance to rule 103 is necessary if the petition is to be

granted, as it would result in the resumption of the use of

petitioner’s maiden name and surname.

ISSUE:

Whether or not in

the case of annulment of marriage, or divorce under the Code of

Muslim Personal Laws of the Philippines, and the husband is married

again to another woman and the former desires to resume her maiden

name or surname, is she required to file a petition for change of

name and comply with the formal requirements of Rule 103 of the Rules

of Court.

RULING:

NO. When a woman

marries a man, she need not apply and/or seek judicial authority to

use her husband's name by prefixing the word "Mrs." before

her husband's full name or by adding her husband's surname to her

maiden first name. The law grants her such right (Art. 370, Civil

Code). Similarly, when the marriage ties or vinculum no longer exists

as in the case of death of the husband or divorce as authorized by

the Muslim Code, the widow or divorcee need not seek judicial

confirmation of the change in her civil status in order to revert to

her maiden name as the use of her former husband's name is optional

and not obligatory for her. When petitioner married her husband, she

did not change her name but only her civil status. Neither was she

required to secure judicial authority to use the surname of her

husband after the marriage, as no law requires it. The use of the

husband's surname during the marriage, after annulment of the

marriage and after the death of the husband is permissive and not

obligatory except in case of legal separation.

The court finds the

petition to resume the use of maiden name filed by petitioner before

the respondent court a superfluity and unnecessary proceeding since

the law requires her to do so as her former husband is already

married to another woman after obtaining a decree of divorce from her

in accordance with Muslim laws.

Articles 209-213.

Miguel R. Unson III,

petitioner, v. Hon. Pedro C. Navarro And Edita N. Araneta,

respondents.

G.R. No. L-52242, 17

November 1980

Facts:

On 19 April 1971,

Miguel and Edita were married. By 1 December 1971, Edita bore their

daughter named Maria Teresa Unson. Since June 1972, the petitioner

and private respondent were living separately. On 13 July 1974, the

respondent judge presided the judicial agreement of the couple for

the separation of properties and live separately. The agreement do

not contain any provision regarding the custody of the child since

they have their own separate arrangement.

In the early part of

1978, the petitioner found out the following information regarding

his wife: (1) she was in a relation with her brother-in-law and

godfather of their child (a former seminarian at that), Maria Teresa;

(2) that the brother-in-law was being treated for manic depressive

disorder; (3) the illicit affair produced 2 children; and (4) that

Edita and her brother-in-law embraced a Protestant faith.

On 28 December 1979,

the respondent judge ordered the petitioner to produce the child,

Maria Teresa Unson, his daughter barely eight years of age, with

private respondent Edita N. Araneta and return her to the custody of

the later, further obliging petitioner to "continue his support

of said daughter by providing for her education and medical needs,"

allegedly issued without a "hearing" and the reception of

testimony in violation of Section 6 of Rule 99.

Issue:

Can the child stay

with her mother given the immoral relationship the mother entered

into?

Held:

No. The Court ruled

it is in the best interest that the child Maria Teresa no longer stay

with her mother given the immoral situation the mother entered into.

The Court granted that the child stay with the petitioner.

Article 173.

Marquino vs

Intermediate Appellate Court (IAC, now Court of Appeals)

Eutiquio Marquino

and Maria Terenal-Marquino (wife) survived by Luz Marquino, Ana

Marquino and Eva Marquino “legitimate children” (Petitioners) v.

Bibiana Romano-Pagadora survived by Pedro, Emy, June, Edgar, May,

Mago, Arden and Mars Pagadora (Respondents)

GR No. 72078, 27

June 1994

Facts:

Respondent Bibiana

filed action for Judicial Declaration of Filiation, Annulment of

Partition, Support and Damages against Eutiquio. Bibiana was born on

December 1926 allegedly of Eutiquio and in that time was single. It

was alleged that the Marquino family personally knew her since she

was hired as domestic helper in their household at Dumaguete. She

likewise received financial assistance from them hence, she enjoyed

continuous possession of the status of an acknowledged natural child

by direct and unequivocal acts of the father and his family. The

Marquinos denied all these. Respondent was not able to finish

presenting her evidence since she died on March 1979 but the sue for

compulsory recognition was done while Eutiquio was still alive. Her

heirs were ordered to substitute her as parties-plaintiffs.

Petitioners,

legitimate children of Eutiquio, assailed decision of respondent

court in holding that the heirs of Bibiana, allegedly a natural child

of Eutiquio, can continue the action already filed by her to compel

recognition and the death of the putative parent will not extinguish

such action and can be continued by the heirs substituting the said

deceased parent.

Issues:

1. Can the right of

action for acknowledgment as a natural child be transmitted to the

heirs?; and

2. Can Article 173

can be given retroactive effect?

Held:

SC ruled that right

of action for the acknowledgment as a natural child can never be

transmitted because the law does not make any mention of it in any

case, not even as an exception. The right is purely a personal one to

the natural child. The death of putative father in an action for

recognition of a natural child can not be continued by the heirs of

the former since the party in the best position to oppose the same is

the putative parent himself.

Such provision of

the Family Code cannot be given retroactive effect so as to apply in

the case at bar since it will prejudice the vested rights of

petitioners transmitted to them at the time of death of their father.

IAC decision was

reversed and set aside. Complaint against Marquinos dismissed.

Article 143-146.

SUSAN NICDAO CARIÑO,

petitioner, v. SUSAN YEE CARIÑO, respondent.

G.R. No. 132529, 2

February 2001

Facts:

In 1969 SPO4

Santiago Cariño married Susan Nicdao Cariño. He had 2 children with

her. In 1992, SPO4 contracted a second marriage, this time with Susan

Yee Cariño. In 1988, prior to his second marriage, SPO4 is already

bedridden and he was under the care of Yee. In 1992, he died 13 days

after his marriage with Yee. Thereafter, the spouses went on to claim

the benefits of SPO4. Nicdao was able to claim a total of P140,000.00

while Yee was able to collect a total of P21,000.00. In 1993, Yee

filed an action for collection of sum of money against Nicdao. She

wanted to have half of the P140k. Yee admitted that her marriage with

SPO4 was solemnized during the subsistence of the marriage b/n SPO4

and Nicdao but the said marriage between Nicdao and SPO4 is null and

void due to the absence of a valid marriage license as certified by

the local civil registrar. Yee also claimed that she only found out

about the previous marriage on SPO4’s funeral.

Issue:

Whether or not the

absolute nullity of marriage may be invoked to claim presumptive

legitimes.

Held:

The marriage between

Nicdao and SPO4 is null and void due the absence of a valid marriage

license. The marriage between Yee and SPO4 is likewise null and void

for the same has been solemnized without the judicial declaration of

the nullity of the marriage between Nicdao and SPO4. Under Article 40

of the FC, the absolute nullity of a previous marriage may be invoked

for purposes of remarriage on the basis solely of a final judgment

declaring such previous marriage void. Meaning, where the absolute

nullity of a previous marriage is sought to be invoked for purposes

of contracting a second marriage, the sole basis acceptable in law,

for said projected marriage to be free from legal infirmity, is a

final judgment declaring the previous marriage void. However, for

purposes other than remarriage, no judicial action is necessary to

declare a marriage an absolute nullity. For other purposes, such as

but not limited to the determination of heirship, legitimacy or

illegitimacy of a child, settlement of estate, dissolution of

property regime, or a criminal case for that matter, the court may

pass upon the validity of marriage even after the death of the

parties thereto, and even in a suit not directly instituted to

question the validity of said marriage, so long as it is essential to

the determination of the case. In such instances, evidence must be

adduced, testimonial or documentary, to prove the existence of

grounds rendering such a previous marriage an absolute nullity. These

need not be limited solely to an earlier final judgment of a court

declaring such previous marriage void.

The SC ruled that

Yee has no right to the benefits earned by SPO4 as a policeman for

their marriage is void due to bigamy; she is only entitled to

properties, money etc owned by them in common in proportion to their

respective contributions. Wages and salaries earned by each party

shall belong to him or her exclusively (Art. 148 of FC). Nicdao is

entitled to the full benefits earned by SPO4 as a cop even if their

marriage is likewise void. This is because the two were capacitated

to marry each other for there were no impediments but their marriage

was void due to the lack of a marriage license; in their situation,

their property relations is governed by Art 147 of the FC which

provides that everything they earned during their cohabitation is

presumed to have been equally contributed by each party – this

includes salaries and wages earned by each party notwithstanding the

fact that the other may not have contributed at all.

Article 107.

SPOUSES ELISEO F.

ESTARES and ROSENDA P. ESTARES, petitioners, v. COURT OF APPEALS,

HON. DAMASO HERRERA as Presiding Judge of the RTC, Branch 24, Biñan,

Laguna PROMINENT LENDING & CREDIT CORPORATION, PROVINCIAL SHERIFF

OF LAGUNA and Sheriff IV ARNEL G. MAGAT, respondents.

G.R. No. 144755, 8

June 2005

Facts:

The spouses Estares

secured a loan of P800k from Prominent Lending & Credit

Corporation (PLCC) in 1998. To secure the loan, they mortgaged a

parcel of land. They however only received P637k as testified by

Rosenda Estares in court. She did not however question the

discrepancy. At that time, her husband was in Algeria working. The

loan eventually went due and the spouses were unable to pay. So PLCC

petitioned for an extrajudicial foreclosure. The property was

eventually foreclosed.

Now, the spouses are

questioning the validity of the loan as they alleged that they agreed

to an 18% per annum interest rate but PLCC is now charging them 3.5%

interest rate per month; they also questioned the terms of the loan.

PLCC argued that the

spouses were properly apprised of the terms of the loan. On the

procedural aspect, PLCC claims that the petition filed by the spouses

is invalid because the certification of non-forum shopping was only

signed by Rosenda and her husband did not sign.

ISSUE:

Whether or not the

petition filed by the spouses is valid.

HELD:

Yes, but their

petition shall not prosper due to substantial grounds. The spouses

were properly apprised by the terms of the loan; they did not

question the terms of the loan when they had the opportunity when it

did not yet mature. Rosenda even acknowledged the terms of the loan

in court.

On the procedural

aspect, even though Eliseo did not sign the certification (because he

was in Algeria), there is still substantial compliance with the

rules. After all they share a common interest in the property

involved since it is conjugal property, and the petition questioning

the propriety of the decision of the Court of Appeals originated from

an action brought by the spouses, and is clearly intended for the

benefit of the conjugal partnership. Considering that the husband was

at that time an overseas contract worker working in Algeria, whereas

the petition was prepared in Sta. Rosa, Laguna, a rigid application

of the rules on forumshopping that would disauthorize the wife’s

signing the certification in her behalf and that of her husband is

too harsh and clearly uncalled for.

Article 91.

FRANCISCO MUÑOZ,

JR., Petitioner, v. ERLINDA RAMIREZ and ELISEO CARLOS, Respondents

G.R. No. 156125, 25

August 2010

FACTS:

The residential lot

in the subject property was registered in the name of Erlinda

Ramirez, married to Eliseo Carlos (respondents). On 6 April 1989,

Eliseo, a Bureau of Internal Revenue employee, mortgaged said lot,

with Erlinda’s consent, to the GSIS to secure a P136,500.00 housing

loan, payable within twenty (20) years, through monthly salary

deductions of P1,687.66. The respondents then constructed a

thirty-six (36)-square meter, two-story residential house on the lot.

On 14 July 1993, the title to the subject property was transferred to

the petitioner by virtue of a Deed of Absolute Sale, dated 30 April

1992, executed by Erlinda, for herself and as attorney-in-fact of

Eliseo, for a stated consideration of P602,000.00.

On 24 September

1993, the respondents filed a complaint with the RTC for the

nullification of the deed of absolute sale, claiming that there was

no sale but only a mortgage transaction, and the documents

transferring the title to the petitioner’s name were falsified. The

respondents presented the results of the scientific examination

conducted by the National Bureau of Investigation of Eliseo’s

purported signatures in the Special Power of Attorney dated 29 April

1992 and the Affidavit of waiver of rights dated 29 April 1992,

showing that they were forgeries. The petitioner, on the other hand,

introduced evidence on the paraphernal nature of the subject property

since it was registered in Erlinda’s name.

The RTC ruled for

petitioner finding that the property is paraphernal and consequently,

the NBI finding that Eliseo’s signatures in the special power of

attorney and in the affidavit were forgeries was immaterial because

Eliseo’s consent to the sale was not necessary. The CA reversed and

held that pursuant to the second paragraph of Article 158 of the

Civil Code and Calimlim-Canullas v. Hon. Fortun, the subject

property, originally Erlinda’s exclusive paraphernal property,

became conjugal property when it was used as collateral for a housing

loan that was paid through conjugal funds – Eliseo’s monthly

salary deductions.

ISSUE:

Whether the subject

property is paraphernal orconjugal

HELD:

The property is

paraphernal property of Erlinda.

As a general rule,

all property acquired during the marriage, whether the acquisition

appears to have been made, contracted or registered in the name of

one or both spouses, is presumed to be conjugal unless the contrary

is proved. In the present case, clear evidence that Erlinda inherited

the residential lot from her father has sufficiently rebutted this

presumption of conjugal ownership pursuant to Articles 92and 109 of

the Family Code. The residential lot, therefore, is Erlinda’s

exclusive paraphernal property.

Moreover, we cannot

subscribe to the CA’s misplaced reliance on Article 158 of the

Civil Code and Calimlim-Canullas. As the respondents were married

during the effectivity of the Civil Code, its provisions on conjugal

partnership of gains (Articles 142 to 189) should have governed their

property relations. However, with the enactment of the Family Code on

3 August 1989, the Civil Code provisions on conjugal partnership of

gains, including Article 158, have been superseded by those found in

the Family Code (Articles 105 to 133).

Article 120 of the

Family Code, which supersedes Article 158 of the Civil Code, provides

the solution in determining the ownership of the improvements that

are made on the separate property of the spouses, at the expense of

the partnership or through the acts or efforts of either or both

spouses. Applying the said provision to the present case, we find

that Eliseo paid a portion only of the GSIS loan through monthly

salary deductions. From 6 April 1989 to 30 April 1992, Eliseo paid

about P60,755.76, not the entire amount of the GSIS housing loan plus

interest, since the petitioner advanced the P176,445.27 paid by

Erlinda to cancel the mortgage in 1992. Considering the P136,500.00

amount of the GSIS housing loan, it is fairly reasonable to assume

that the value of the residential lot is considerably more than

theP60,755.76 amount paid by Eliseo through monthly salary

deductions. Thus, the subject property remained the exclusive

paraphernal property of Erlinda at the time she contracted with the

petitioner; the written consent of Eliseo to the transaction was not

necessary. The NBI finding that Eliseo’s signatures in the special

power of attorney and affidavit were forgeries was immaterial.

Nonetheless, the RTC

and the CA apparently failed to consider the real nature of the

contract between the parties (where the SC found that the contract is

an equitable mortgage and not one of sale).

Article 75.

Minoru Fujiki,

Petitioner, v. Maria Paz Galela Marinay, Shinichi Maekara, Local

Civil Registrar Of Quezon City, And The Administrator And Civil

Registrar General Of The National Statistics Office, Respondents.

G.R. No. 196049, 26

June 2013

Facts:

In January 2004,

Minoru Fujiki, a Japanese citizen, married Maria Paz Marinay, a

Filipino, here in the Philippines. But in May 2008, Marinay, while

her marriage with Fujiki was still subsisting, married another

Japanese citizen (Shinichi Maekara), here in the Philippines. Marinay

and Maekara later went to Japan.

In 2010, Fujiki and

Marinay reconciled and decided to resurrect their love affair. Fujiki

helped Marinay obtain a Japanese judgment declaring Marinay’s

marriage with Maekara void on the ground of bigamy. Said decree was

granted in the same year. Fujiki and Marinay later went back home to

the Philippines together.

In 2011, Fujiki went

to the RTC of Quezon City and filed a petition entitled “Judicial

Recognition of Foreign Judgment (or Decree of Absolute Nullity of

Marriage)“. He filed the petition under Rule 108 of the Rules of

Court (Cancellation Or Correction Of Entries In The Civil Registry).

Basically, Fujiki wanted the following to be done:

(1) the Japanese

Family Court judgment be recognized;

(2) that the

bigamous marriage between Marinay and Maekara be declared void ab

initio under Articles 35(4) and 41 of the Family Code of the

Philippines; and

(3) for the RTC to

direct the Local Civil Registrar of Quezon City to annotate the

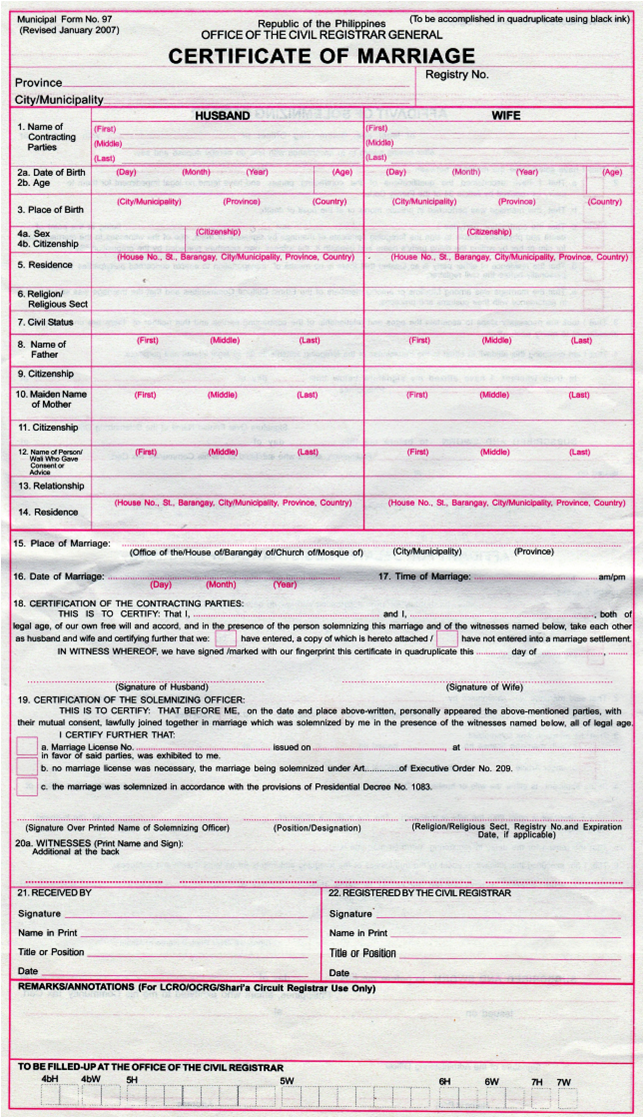

Japanese Family Court judgment on the Certificate of Marriage between

Marinay and Maekara and to endorse such annotation to the Office of

the Administrator and Civil Registrar General in the National

Statistics Office (NSO).

The RTC dismissed

the petition on the ground that what Fujiki wanted is to have the

marriage between Marinay and Maekara be declared null (hence a

petition for declaration of nullity of marriage); that under A.M. No.

02-11-10-SC or the “Rule on Declaration of Absolute Nullity of Void

Marriages and Annulment of Voidable Marriages”, a petition for such

may only be filed by the husband or wife or in this case either

Maekara or Marinay only.

Issue:

Whether or not the

RTC is correct.

Held:

No. A.M. No.

02-11-10-SC is not applicable here. What’s applicable is Rule 108

of the Rules of Court. As aptly commented by the Solicitor General:

Rule 108 of the

Rules of Court is the procedure to record “[a]cts, events and

judicial decrees concerning the civil status of persons” in the

civil registry as required by Article 407 of the Civil Code. In other

words, “[t]he law requires the entry in the civil registry of

judicial decrees that produce legal consequences upon a person’s

legal capacity and status x x x.” The Japanese Family Court

judgment directly bears on the civil status of a Filipino citizen and

should therefore be proven as a fact in a Rule 108 proceeding.

Thus:

The Rule on

Declaration of Absolute Nullity of Void Marriages and Annulment of

Voidable Marriages (A.M. No. 02-11-10-SC) does not apply in a

petition to recognize a foreign judgment relating to the status of a

marriage where one of the parties is a citizen of a foreign country.

Moreover, in Juliano-Llave v. Republic, this Court held that the rule

in A.M. No. 02-11-10-SC that only the husband or wife can file a

declaration of nullity or annulment of marriage “does not apply if

the reason behind the petition is bigamy.”

But how will

Fujiki’s petition in the RTC prosper?

Fujiki needs to

prove the foreign judgment as a fact under the Rules of Court. To be

more specific, a copy of the foreign judgment may be admitted in

evidence and proven as a fact under Rule 132, Sections 24 and 25, in

relation to Rule 39, Section 48(b) of the Rules of Court.

Fujiki may prove the

Japanese Family Court judgment through

(1) an official

publication or

(2) a certification

or copy attested by the officer who has custody of the judgment. If

the office which has custody is in a foreign country such as Japan,

the certification may be made by the proper diplomatic or consular

officer of the Philippine foreign service in Japan and authenticated

by the seal of office.

Article 59.

Benjamin Bugayong,

plaintiff-appellant, v. Leonila Ginez, defendant-appellee.

G.R. No. L-10033, 28

December 1956

Facts:

On 27 August 1949,

Benjamin Bugayong married Leonila Ginez at Asingan, Pangasinan.

Before he left to continue his work as a US Navy service, he and

Leonila stayed at Sampaloc, Manila with his sisters. By July 1951,

Leonila left the dwelling of her sister-in-law and informed her

husband she will be with her mother in Asingan, Pangasinan. Later,

she went to Dagupan City to study in a local college.

Benjamin has been

receiving letters since July 1951 that Leonila is having an affair

with another man, a certain ‘Eliong’.

In August 1952,

Benjamin returned to the Philippines, went to Pangasinan and sought

for his wife whom he met in the house of Leonila’s godmother. They

lived again as husband and wife and stayed in the house of Pedro

Bugayong, cousin of the plaintiff-husband. On the second day, he

tried to verify from his wife the truth of the information he

received but instead of answering, Leonila packed up and left him

which Benjamin concluded as a confirmation of the acts of infidelity.

After he tried to locate her and upon failing he went to Ilocos

Norte. Benjamin filed in the Court of the First Instance (CFI) of

Pangasinan a complaint for legal separation against Leonila, who

timely filed an answer vehemently denying the averments of the

complaint.

Issue:

Whether or not the

acts charged in line with the truth of allegations of the commission

of acts of infidelity amounting to adultery have been condoned by the

plaintiff-husband.

Held:

Granting that

infidelities amounting to adultery were commited by the wife, the act

of the husband in persuading her to come along with him and the fact

that she went with him and together they slept as husband and wife

deprives him as the alleged offended spouse of any action for legal

separation against the offending wife because his said conduct comes

within the restriction of Article 100 of Civil Code.

Condonation is the

conditional forgiveness or remission, by a husband or wife of a

matrimonial offense which the latter has committed.

Article 43.

Facts:

On 26 October

2000,Rita Quiao filed a complaint for legal separation against

Brigido Quiao. The RTC ruled in favor of Rita with all their

underaged children staying with Rita except Letecia who was of legal

age.

Their acquired

properties will be divided between the respondents and the

petitioners subject to the respective legitimes of the children and

the payment of the unpaid liabilities of PhP 45,740. The Petitioner's

share of the net profits earned by the conjugal partnership is

forfeited in favor of the common children.

No Motion of

Reconsideration or appeal was filed. By 12 December 2005, Petitioners

filed for a motion of execution which the trial court granted, and a

writ was issued. It was partially executed on 06 July 2006.

On 07 July 2006, or

after more than 9 months from the promulgation of the decision, the

petitioner filed before the RTC a Motion for Clarification, asking

the RTC to define the term “Net Profits Earned.”

Thus, the RTC

explained that the phrase “NET PROFIT EARNED” denotes “the

remainder of the properties of the parties after deducting the

separate properties of each [of the] spouse and the debts.” The

Order further held that after determining the remainder of the

properties, it shall be forfeited in favor of the common children

because the offending spouse does not have any right to any share of

the net profits earned, pursuant to Articles 63, No. (2) and 43, No.

(2) of the Family Code. Thus, the RTC said that there was no blatant

disparity when the sheriff intended to forfeit all the remaining

properties after deducting the payments of the debts, because only

separate properties of the Brigido shall be delivered to him which he

has none.

Not satisfied with

the Order, the Brigido filed an MR. Consequently, the RTC issued

another Order dated 08 November 2006, holding that although the

Decision dated 10 October 2005 has become final and executory, it may

still consider the Motion for Clarification because Brigido simply

wanted to clarify the meaning of “net profit earned.”

Furthermore, the same Order held:

ALL TOLD, the Court

Order dated 31 August 2006 is hereby ordered set aside. NET PROFIT

EARNED, which is subject of forfeiture in favor of [the] parties'

common children, is ordered to be computed in accordance [with] par.

4 of Article 102 of the Family Code.

Thereafter, Rita

filed an MR praying for the correction and reversal of the Order

dated 08 November 2006. Thereafter, on 08 January 2007, the trial

court had changed its ruling again and granted the respondents' MR

whereby the Order dated 08 November 2006 was set aside to reinstate

the Order dated 31 August 2006. Not satisfied with the trial court's

Order, Brigido filed on 27 February 2007 this instant Petition for

Review under Rule 45.

Issue:

1) What law governs

the dissolution and liquidation of the common properties of a couple

who got married in 1977 (before the Family Code was enacted) and

obtained a decree of legal separation when the Family Code is already

in effect?

2) Can the Family

Code be given retroactive effect for purposes of determining the net

profits to forfeited as a result of the decree of legal separation

without impairing vested rights acquired under the Old Civil Code?

Held:

1) Article 129 of

the Family Code in relation to Article 63(2) of the Family Code.

2) No, it cannot be

given retroactive effect if it will impair vested rights. However,

the Family Code applies in the instant case because there is no

vested right that will be impaired. (based on Article 256 of the

Family Code which provides for retroactivity except when vested

rights will be impaired).

A vested right is

one whose existence, effectivity and extent do not depend upon events

foreign to the will of the holder, or to the exercise of which no

obstacle exists, and which is immediate and perfect in itself and not

dependent upon a contingency. It expresses the concept of present

fixed interest which, in right reason and natural justice, should be

protected against arbitrary State action, or innately just and

imperative right which enlightened free society, sensitive to

inherent and irrefragable individual rights, cannot deny.

Article 27.

Arsenio De Loria and

Ricarda De Loria v. Felipe Apellan Felix

G.R. No. L-9005, 20

June 1958

Facts:

Before World War II,

Matea dela Cruz and Felipe Apellan Felix were living for quite some

time as husband and wife though without the sanctity of marriage.

They acquired properties together but had no children.

Right after the

liberation of Manila, Matea got ill. While being doing a confession

to Father Gerardo Bautista,a Catholic priest, she admitted that she

and Felipe were never married. Upon strong urging of the priest, they

agreed. After the confession, Holy Communion, Sacrament of Extreme

Unction, Father Bautista solemnized the union of the two, in articulo

mortis, with Carmen Ordiales and Judith Vizcarra as sponsors or

witness . The date was either 29 or 30 January 1945.

Matea recovered from

her illness for a few months but eventually died on January 1946,

with Fr. Bautista performing the burial ceremonies.

On 12 May 1952,

Arsenio de Loria and Ricarda de Loria, grand nephew and niece,

respectively, of Matea by her sister Adriana dela Cruz, filed a

complaint against Felipe to compel him to account and turnover the

properties left by their grand aunt Matea. Felipe responded that he

was the widower of the late Matea, therefore, the rightful claimant.

The Court of First Instance gave a favorable judgment for the

petitioners, but on appeal to the Court of Appeals (CA) reversed and

dismissed the complaint.

The petitioners

appealed the decision of the CA citing that the marriage of Felipe

and Matea, though solemnized by a Catholic priest, was not registered

to the local civil registrar.

Issue:

Is a marriage

between two parties legal though no marriage license were issued?

Ruling:

Yes, according to

the Supreme Court. In the old Marriage Law, failure to sign the

marriage contract is not a cause of annulment.

Bearing in mind that

the "essential requisites for marriage are the legal capacity of

the contracting parties and their consent" (section 1 of the old

Marriage Law), the latter being manifested by the declaration of "the

parties" "in the presence of the person solemnizing the

marriage and of two witnesses of legal age that they take each other

as husband and wife" — which in this case actually occurred.

The Supreme Court opined that the signing of the marriage contract or

certificate was required by the statute simply for the purpose of

evidencing the act. No statutory provision or court ruling has been

cited making it an essential requisite — not the formal requirement

of evidentiary value. The fact of marriage is one thing; the proof by

which it may be established is quite another.

Father Bautista was

at fault for not registering the formal union of the couple to the

local civil registrar. This does not mean that the non-registration

of the marriage is a ground for annulment. Therefore, the married

couple should not suffer for the omission of Father Bautista.

Felipe is the

rightful claimant to the estate of Matea -being the husband. As such,

the claims of the petitioner was denied.

Article 11.

Comments

Post a Comment